I remember visiting a small exhibition of Rouault's works at the Royal Academy in London.

One of which was a life size picture of a man stripped, bare, standing looking out. The painting was hung at human height, giving the impression of a mirror. You stood before it and was looked at by yourself. For the self in the painting was the man Jesus, utterly alone, abandoned by his friends, judged, awaiting death - behold the man, every man. I stood awhile, watching people, coming in front of the painting, and everyone, who let it bear scrutiny, was changed. The change was completely noticeable in the way they carried themselves, in the way they looked from then on. The shifts in body and timing were subtle but real.

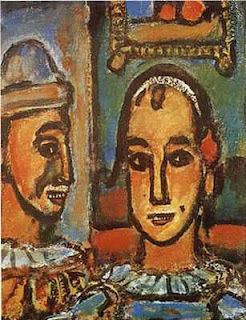

In this painting Rouault had captured both the complete humanity of the self - the capacity of its exile and in having that exile shared by this particular man: a path restored home.

I was reminded here of Durckheim. One of his recurring themes was the 'acceptance of the unacceptable' - if we can step into what appears a dead end, and fully embrace it, it is paradoxically at that point that a way can be opened up to transformation.

In this painting of Rouault's it seems to suggest that it is only when we recognize our complete aloneness that we can break through to a recognition of our complete identification with others: the common humanity that Christ our self bears. There is a beautiful passage that I half remember from a Buddhist teacher that it is only when you utterly taste your aloneness that you are truly able to offer everything to all.

Rouault is an intense painter of the human: a humanity that never steps out of the possibility of redemption; however, distantly we pass into either our own grieved loneliness or our own enclosing pride. There is nowhere we can go away from ourselves that does not bring us back to a confrontation with ourselves. There is no place to hide.

Comments

Post a Comment